At first glance, a bolt may seem like a very simple item that holds things together. But dig a bit deeper and you’ll realise there’s more behind seemingly insignificant bolt and screws than first meets the eye. Without them, all our gadgets and machines would fall to pieces.

First published in Bolted #2 2012.

Bolts are one of the most common elements used in construction and machine design. They hold everything together – from screws in electric toothbrushes and door hinges to massive bolts that secure concrete pillars in buildings. Yet, have you ever stopped to wonder where they actually came from?

While the history of threads can be traced back to 400 BC, the most significant developments in the modern day bolt and screw processes were made during the last 150 years. Experts differ as to the origins of the humble nut and bolt. In his article “Nuts and Bolts”, Frederick E. Graves argues that a threaded bolt and a matching nut serving as a fastener only dates back to the 15th century. He bases this conclusion on the first printed record of screws appearing in a book in the early 15th century.

However, Graves also acknowledges that even though the threaded bolt dates back to the 15th century, the unthreaded bolt goes back to Roman times when it was used for “barring doors, as pivots for opening and closing doors and as wedge bolts: a bar or a rod with a slot in which a wedge was inserted so that the bolt could not be moved.” He also implies that the Romans developed the first screw, which was made out of bronze, or even silver. The threads were filed by hand or consisted of a wire wound around a rod and soldered on.

According to bolt expert Bill Eccles’ research, the history of the screw thread goes back much further. Archimedes (287 BC–212 BC) developed the screw principle and used it to construct devices to raise water. However, there are signs that the water screw may have originated in Egypt before the time of Archimedes. It was constructed from wood and was used to irrigate

land and remove bilge water from ships. “But many consider that the screw thread was invented around 400 BC by [Greek philosopher] Archytas of Tarentum, who has often been called the founder of mechanics and considered a contemporary of Plato,” Eccles writes on his website.

The history can be broken down into two parts: the threads themselves that date back to around 400 BC when they were used for items such as a spiral for lifting water, presses for grapes to make wine, and the fasteners themselves, which have been in use for around 400 years.

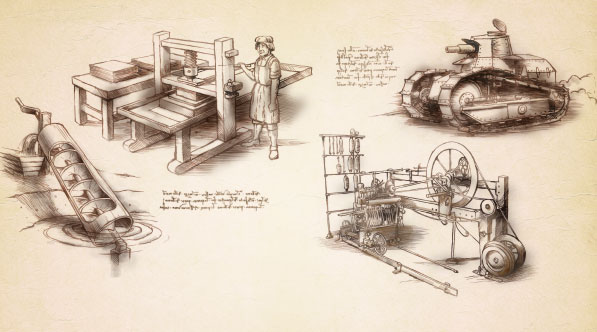

Moving forward to the 15th century, Johann Gutenberg used screws in the fastenings on his printing presses. The tendency to use screws gained momentum with their use being extended to items such as clocks and armour. According to Graves, Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks from the late 15th and early 16th centuries include several designs for screw-cutting machines.

What the majority of researchers on this topic do agree on, though, is that it was the Industrial Revolution that sped up the development of the nut and bolt and put them firmly on the map as an important component in the engineering and construction world.

The “History of the Nut and Bolt Industry in America” by W.R. Wilbur in 1905 acknowledges that the first machine for making bolts and screws was made by Besson in France in 1568, who later introduced a screw-cutting gauge or plate to be used on lathes. In 1641, the English firm, Hindley of York, improved this device and it became widely used.

Across the Atlantic in the USA, some of the documented history of the bolt may be found in the Carriage Museum of America. Nuts on vehicles built in the early 1800s were flatter and squarer than later vehicles, which had chamfered corners on the nuts and the flush was trimmed off the bolts. Making bolts at this time was a cumbersome and painstaking process.

Initially, screw threads for fasteners were made by hand but soon, due to a significant increase in demand, it was necessary to speed up the production process. In Britain in 1760, J and W Wyatt introduced a factory process for the mass production of screw threads. However, this milestone led to another challenge: each company manufactured its own threads, nuts and bolts so there was a huge range of different sized screw threads on the market, causing problems for machinery manufacturers.

It wasn’t until 1841 that Joseph Whitworth managed to find a solution. After years of research collecting sample screws from many British workshops, he suggested standardising the size of the screw threads in Britain so that, for example, someone could make a bolt in England and someone in Glasgow could make the nut and they would both fit together. His proposal was that the angle of the thread flanks was standardised at 55 degrees, and the number of threads per inch, should be defined for various diameters.

While this issue was being addressed in Britain, the Americans were trying to do likewise and initially started using the Whitworth thread.

In 1864, William Sellers proposed a 60 degree thread form and various thread pitches for different diameters. This developed into the American Standard Coarse Series and the Fine Series. One advantage the Americans had over the British was that their thread form had flat roots and crests. This made it easier to manufacture than the Whitworth standard, which had rounded roots and crests. It was found, however, that the Whitworth thread performed better in dynamic applications and the rounded root of the Whitworth thread improved fatigue performance.

During World War I, the lack of consistency between screw threads in different countries became a huge obstacle to the war effort; during World War II it became an even bigger problem for the Allied forces. In 1948, Britain, the USA and Canada agreed on the Unified thread as the standard for all countries that used imperial measurements. It uses a similar profile as the DIN metric thread previously developed in Germany in 1919. This was a combination of the best of the Whitworth thread form (the rounded root to improve fatigue performance) and the Sellers thread (60 degree flank angle and flat crests). However, the larger root radius of the Unified thread proved to be advantageous over the DIN metric profile. This led to the ISO metric thread which is used in all industrialised countries today.

Those working in the industry have witnessed much fine-tuning of bolts during recent decades. “When I started in the industry 35 years ago the strength of the bolts was not as fully defined as it is today,” recalls Eccles. “With the introduction of the modern metric property classes and the recent updates to the relevant ISO standards, the description of a bolt’s strength and the test methods used to establish their properties is now far better defined.”

As the raw materials industry has become more sophisticated, the DNA of bolts has changed from steel to other more exotic materials to meet changing industry needs.

Over the last 20 years there have been developments in nickel-based alloys that can work in high temperature environments such as turbochargers and engines in which steel doesn’t perform as well. Recent research focuses on light metal bolts such as aluminum, magnesium and titanium.

Today’s bolt technology has come a long way since the days when bolts and screws were made by hand and customers could only choose between basic steel nuts and bolts. These days, companies like Nord-Lock have invented significant improvements in bolting technology, including wedge-locking systems. Customers can select pre-assembled zinc flake coated or stainless steel washers, wheel nuts designed for flat-faced steel rims, or combi bolts, which are customised for different applications. The acquisition of US company Superbolt Inc. and Swiss company P&S Vorspannsysteme AG (today Nord-Lock AG) has added bolting products used in heavy industry, such as offshore, energy, and mining, to Nord-Lock’s portfolio, taking a huge step in becoming a world leader in bolt securing.

There is also much more emphasis now on analysing joints. “In the past, people used to decide upon a certain size of fastener based on their experience alone. And, fingers crossed, it would work,” Eccles explains. “Nowadays, people focus more on analysis and making sure things work before products are built and sent out into the market.”